Oct. 14, 2022

Why the time is now to address the growing concern surrounding this inadequately trained niche workforce.

Mike Grennier

While the DC power industry has more than its fair share of challenges, one stands above the rest: the lack of adequately trained stationary battery technicians.

A recent study of data center outages by the Uptime Institute estimates that almost two-thirds of all unplanned outages are associated with human error. Most of these events occur when technicians failed to satisfactorily complete a defined operational procedure. While this study covered data centers, all indications suggest that this trend may well apply across many industries where technicians are required to carry out mission-critical, procedural-based tasks.

Who’s at fault when it comes to human error on the job? Are technicians on the front lines or employers ultimately responsible for ensuring technicians have the knowledge and skills necessary to adequately perform their jobs?

Regardless of who’s at fault, on a recent episode of the “DC Power Hour” podcast, three respected stationary battery industry experts overwhelmingly agreed that it’s high time the industry addresses this issue and the impending shortage of specialized technicians responsible for ensuring backup power reliability is at its highest level – where it needs to be at all times.

“There is greater reliance on stationary batteries today than there was before, and it’s going to continue to grow,” said Ed Rafter, a 35-year veteran in battery systems, primarily for data centers. “Ensuring the maximum reliability and uptime of a battery as intended requires specialized talent. There are no two ways about it.”

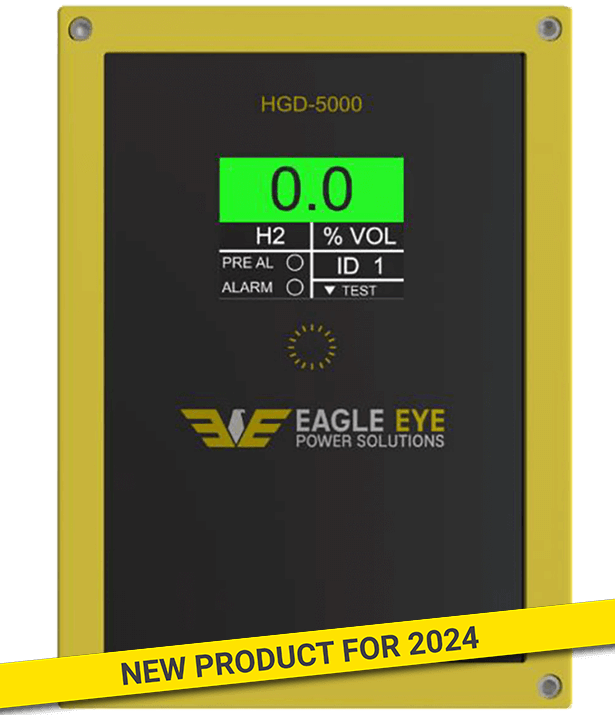

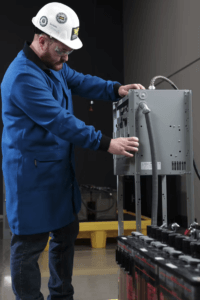

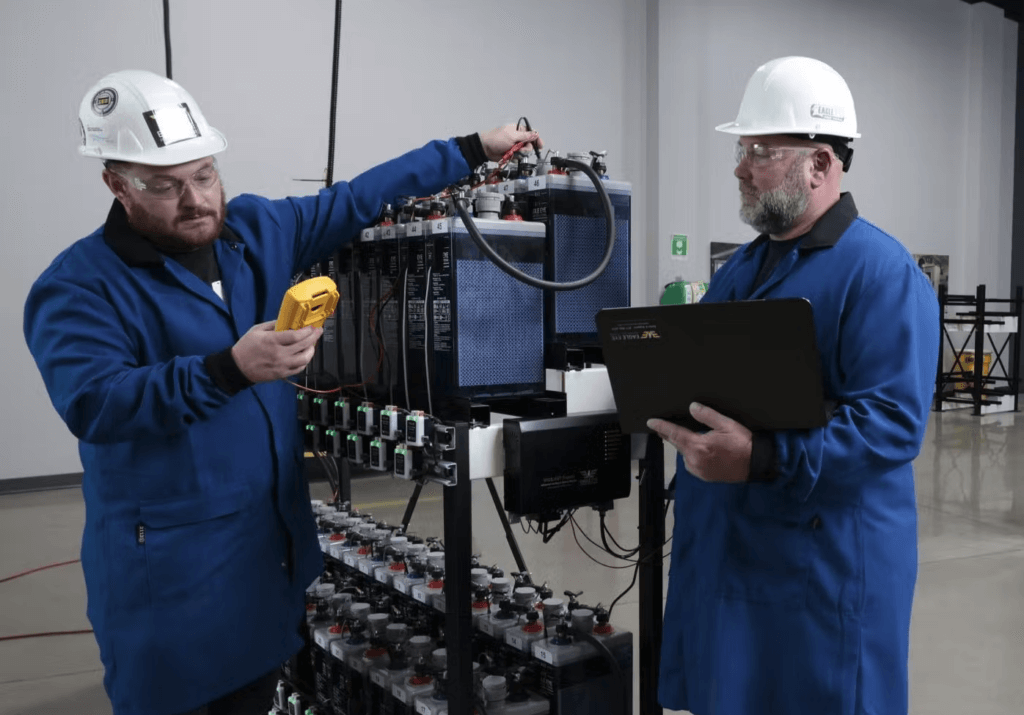

A stationary battery is a far more complex device than most people realize, adds George Pedersen, an instructor with Eagle Eye University (EEU), a stationary battery training subsidiary of Eagle Eye Power Solutions (EEPS) in Mequon, Wisc. “Many [people] have no idea how important they are to their ability to do the things they are supposed to do. They simply don’t understand the importance of training.”

Whether it’s the stationary battery installation, service or maintenance providers, or the end-users themselves, more industry-wide emphasis on training is essential, maintains 40-year industry veteran J. Allen Byrne, an EEPS technical advisor.

“You’ve got to change the attitude of a lot of people,” says Byrne. “It is going to be a challenge. I don’t know how we’re going to do it, but it has to change.”

Standards only go so far

The lack of people specially trained in stationary battery installation and maintenance didn’t happen overnight; it’s been brewing for decades. One of the reasons, according to the experts, has to do with the lack of widespread adoption of industry standards and guides designed to determine the skill levels required by technicians.

Among the U.S. standards is IEEE Standard 1657, IEEE Recommended Practice for Personnel Qualification for Installation and Maintenance of Stationary Batteries. It was developed in the early 2000s by the IEEE Power Engineering Society’s Stationary Battery Committee, now the IEEE Power and Energy Society Energy Storage and Stationary Battery Committee (IEEE PES ESSBC). Another key standard is from the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), which created NERC Standard PRC-005-2 to assess the operational reliability of batteries used in the electrical utility industry.

While all three experts agree that these standards are a step in the right direction, they say standards only go so far when it comes to training because they’re designed primarily to provide guidelines. They do not dictate how training should be implemented.

IEEE 1657 is a prime example of such limitations when it comes to training, note Byrne and Rafter, both of whom helped develop the standard.

“It basically tells you what you should know but not how to do it,” Byrne says of IEEE 1657, which sets a high bar for the required knowledge base for the various technician levels, with an emphasis on safety.

“While 1657 covers everything from a knowledge standpoint, the missing link is in the delivery of training,” says Rafter. “You need trainers, you need instructors, you need people to deliver it, and that’s one of the issues we have now.”

A two-part problem

The lack of people who work as specialized stationary battery technicians is a two-part problem – and one that is common to most technical trades. Part of the problem has to do with a lack of interest in the battery trade in general. The second concerns the steady departure of those in the field with the knowledge and expertise to pass along to the next generation.

“We’re struggling to find qualified technicians, and at the same time, the trainers and the people who know the material are moving on,” says Rafter.

A major issue with qualified people for the job, notes Pedersen, is the absence of a career path for those who choose to work as stationary battery technicians.

“The traditional way to get into this type of technical field would have been apprenticeships,” says Pedersen. “Very few of those exist today. A lot of young people see no real career path there. There’s no structure in place for them to be promoted or moved up in an organization.”

Byrne suggests this problem is exacerbated by old-school experts who are exiting the industry. “People aren’t getting into the field; maybe they don’t see it as glamourous,” says Byrne. “In years past, you learned from the old guy. But there aren’t many left to pass on the knowledge. They were either let go, or they retired and weren’t replaced.”

Profitability is a clear factor

Another major reason for an inadequately trained workforce of battery technicians concerns the drive for profitability across virtually all industries, the experts say.

“In my opinion, it has to do with a ‘financial engineering’ decision,” says Byrne. “Many organizations are saying, ‘If it’s not a profit center, it’s not on the radar.’”

According to Byrne, many place the responsibility for stationary batteries on the person who oversees maintenance for an entire facility. “They want to spread these specialized tasks among the fewest people possible,” says Byrne, emphasizing that, in many cases, this personnel group is responsible for many other non-battery-related tasks.

The competition for business, as well as skilled employees, also plays into the decision not to invest in people who are truly specialized in stationary batteries, notes Rafter.

“How do you make any profit margin without sacrificing something?” says Rafter. “I’m not saying it’s always even intentional, but what are your options? It comes down to money.”

Pedersen says it ties back to the investment needed for things like apprenticeships and more robust training programs that focus on more than simply how to perform tasks.

“There are people out there doing the job, but they don’t necessarily understand why they’re doing it,” says Pedersen. “If you don’t know why, it’s boring; then, it’s likely you won’t do it very accurately. The problem we have is that while battery maintenance may be performed, it’s no longer being done by people who specialize in it.”

Safety and reliability at stake

Although there are a variety of factors behind the shortage of trained stationary battery technicians, the experts say the issue can no longer be swept aside, especially given the importance of stationary battery safety and reliability.

“There can be a lot of ‘gotchas’ if you don’t know what you’re doing,” says Rafter, noting how the issue has taken on even more importance since new battery technologies have been introduced ahead of the final standards for installing and maintaining them. “It’s vital that the person who installs and maintains the batteries understands all the procedures and what’s right and what’s wrong.”

Some of these “gotchas” cited by Rafter, Byrne, and Pedersen include ineffective maintenance and monitoring, damage to systems, and complete system failure.

“The backup power system, whether it’s an uninterruptible power system (UPS) or a DC system, is an Achilles’ heel,” says Byrne. “If it fails, the whole system could be at risk.”

This is one of many issues he’s experienced firsthand with battery installation and maintenance.

“Numerous studies show battery-related failures cause most of the outages and downtime in data centers,” says Byrne. “That can cost millions of dollars.”

Pedersen adds that without proper training in stationary battery maintenance and monitoring, the ability to ensure reliability is in question.

“Take a basic 120V utility battery as an example,” he says. “You might not be able to identify the potential points of failure that can occur within the battery. There are 60 cells in series within that battery. Any one of those 60 cells could fail and effectively take the battery offline.”

In addition to reliability issues, there are major safety concerns. The list of potential accidents caused by inexperience or negligence is lengthy.

“You’ve got a chemical hazard because the electrolytes in the batteries are highly corrosive,” says Pedersen. “You have the potential for electrocution. You have the potential for arc flash. You’ve got the potential for explosion because the batteries generate hydrogen. And batteries made of lead are very heavy; you can have handling accidents with that.”

According to these experts, accidents can cause not only serious physical harm but also death.

“It wasn’t long ago, I knew of someone who got killed on the job,” says Rafter. “It does happen. There is definitely a serious safety issue involved.”

Human error is clearly one of the main reasons why accidents and technical failures with stationary batteries happen, notes Pedersen.

“Human error is very high on the list,” he says. “If you have human error, that’s a clear indication to me that you didn’t have proper training.”

Solutions in the works

There is no one answer for how best to ensure the people who install and maintain stationary batteries are adequately trained and qualified to safely and effectively perform the work required. Yet the answers have to be found.

“We have more stationary batteries today than ever, and there are more coming,” says Rafter. “The importance of training is self-evident.”

He goes on to say the industry needs to find a way to get people interested in the technical trades and take on jobs like that of a stationary battery technician.

“We have to have more qualified people to install and maintain batteries,” says Pedersen. “If someone comes in and puts in their time on the job, they can then learn and advance accordingly. That’s something I’d like to see happen.”

An increase in accountability would go a long way toward addressing the issue, notes Byrne. Accountability, he says, starts with the person performing the work because they need to ensure they receive the proper training. It also applies to the employer who needs to ensure that the person they hired to do the job is adequately trained. The industry might also want to look at other options, such as certification or licensing.

“If you hire an electrician to perform work, for example, they’ve usually gone through an apprenticeship program and worked as a journeyman to get their license,” says Byrne. “I just think there needs to be more accountability.”

Pedersen strongly supports this notion, adding there is no substitute for more well-rounded training at all levels, with or without an apprenticeship.

“We need to change this idea of training some people in the theory of battery installation and maintenance and training other people in how to do battery installation and maintenance,” says Pedersen. “The industry needs to do training both ways. The people in supervisory levels should also learn this on the job. Training is something that’s been neglected, and we have to accept that it’s now more important than ever.”

Mike Grennier is a freelance writer specializing in business-to-business content. This piece was written for Eagle Eye Power Solutions, Mequon, Wis.